Longtime readers of this blog may recall that when I went back into teaching a few years ago, I dealt with enormous ex-activist’s guilt. I felt like I was letting down my fellow advocates in the massively important spaces of women’s rights work and relationship and sexual violence prevention. To this day, those causes are still hugely important to me.

I’m happy to say that I’ve found ways to continue spotlighting those issues, especially by highlighting the roles that women have played in the millennia-old global story of mathematical discovery. I often share with my classes the stories of pioneering women in mathematics, from Hypatia of ancient Alexandria to Ada Lovelace of Victorian England, and from Katherine Johnson of Hidden Figures fame to Dr. Erika Camacho of UT-San Antonio, whose current mathematical work helps researchers to find cures for retinal diseases. I have posters of some of these women around my classroom; I even have a shirt with some of their names.

Last week, I was finally able to create an applicational lesson based on something we’ve been studying in a couple of my classes. I’ve been hoping to do something like this, but I was re-inspired by my friends Naehee Kwun of UC Irvine and Ted Chao of UCLA (pictured), who presented a workshop for Asian American math teachers at a recent conference. They said that we need to show students that math really matters in life. Because I’ve been covering equivalent fractions with some of my students, teaching them how to convert fractions into ones with common denominators so they can compare their sizes accurately, I created this lesson on the gender pay gap.

Dr. Ted Chao, who like me grew up in Houston, also used to be a secondary math teacher; now he teaches at both UCLA and The Ohio State University.

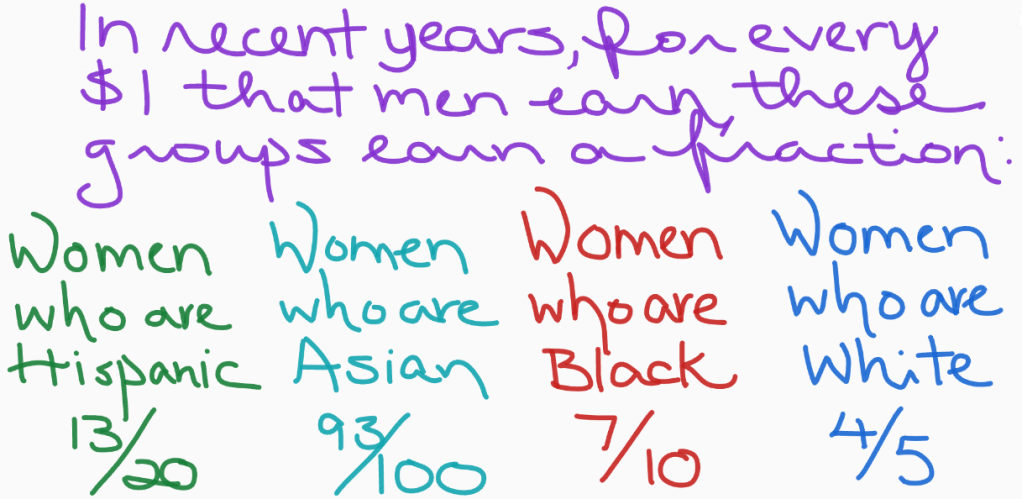

It started like this (and I had to round the numbers a bit to make them workable for my students):

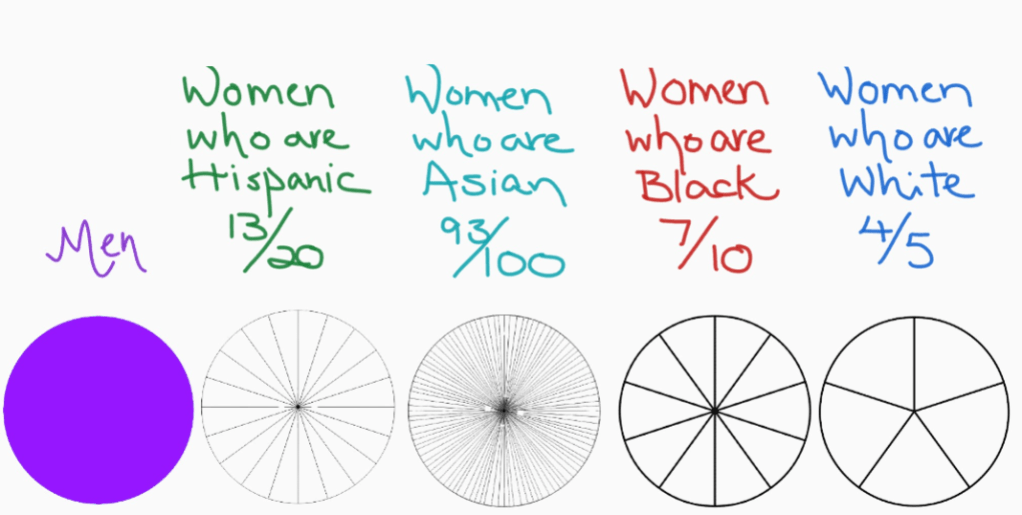

We had colored in pizza charts the previous week, so I asked them to shade in portions of these pizza charts with their corresponding fractions:

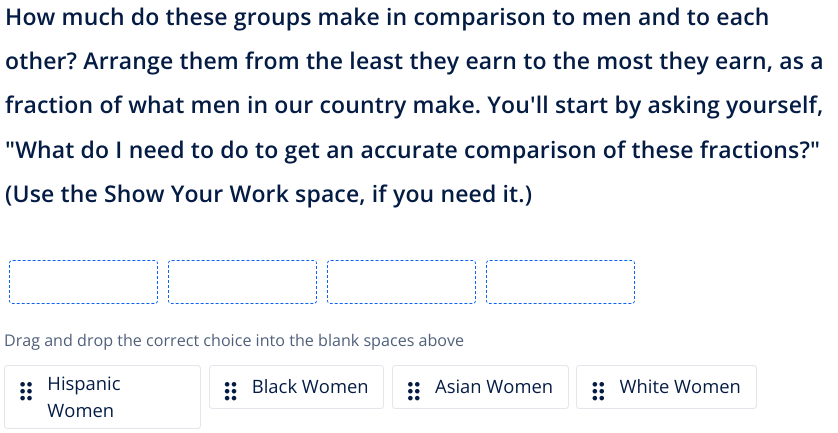

This gave my students a chance to compare visually the sizes of these fractions with each other and with the main point of comparison, men’s salaries. I followed that with an ordering question:

This prompted students to scale up each of the fractions mathematically so they all had the same denominator, enabling a numerical comparison. I then asked students to discuss at their tables, in groups of three or four, possible reasons for this. I solicited their thoughts as an entire class, and their answers ranged from “women usually stay home with the kids” and “education levels play a part” to “men do some jobs better” and “sexism and racism.”

After this, I finally introduced the term gender wage gap itself, showing a relatively recent two-minute video explainer from USA Today. The video, which I’m unable to reproduce here due to my WordPress subscription level, does a good job of quickly covering a bunch of factors causing the wage gap. It’s worth watching!

I followed this by sharing the story of a friend of mine who is a manager in a Fortune 500 corporation; she herself wasn’t sure that there was such a thing as a gender wage gap until she saw the salaries at her company laid out before her. “There it was, plain and simple,” she had told me.

I concluded by asking my students, “What’s one idea that you can take away from this discussion that could be useful to you in the future?” Their answers were quite varied, including “go to college so I can get a good job where they won’t discriminate against me,” “I shouldn’t discriminate against women because I’ve been bullied for my skin color,” “be grateful I’m male,” and “never give up and work harder every day.” From their written responses, a bunch of my students did come away with the understanding that while there are a variety of factors behind the gender wage gap, one of the major reasons is unfairness.

Regardless of their takeaways, I hope they recognize that there is power in mathematics. I told them, “Math is one of the most powerful tools we have for making life better for individuals, communities, and even the world.” This thought reflects a line by Russian American mathematician Edward Frenkel that I heard at the aforementioned math teachers conference:

I really like that. Most immediately, this calls to mind the fact that math skills give people greater freedom in the types of career paths they can take; often, strong math abilities open doors to higher-paying vocations. But Frenkel’s thought applies more broadly, too, because we can use math to shine a light on social problems and to show which solutions are more likely to be helpful. We can use math to keep powerful people and institutions accountable. And we can even use math in fractional form to help high school students to better understand and confront the disparities in wages they will face in the future.

I’m so glad to have found ways to continue my advocacy for women’s rights, even as a math teacher!